Adapted from the article All Students can Read to Learn Science! by Tiffany L. Gallagher, Ph.D. and Xavier Fazio, Ed.D., Brock University

The acquisition of language skills is essential to support ‘reading to learn’ about information in subjects such as science (Fang et al., 2008; Moje, 2008). While learning in science is complimented through hands-on activities, research, and inquiry, many fundamental concepts are acquired by students through reading textbooks, articles, and even their own notes. For today’s students to participate in tomorrow’s decision-making, it is imperative that they possess the skills to be adept at reading, writing, and oral communication in science (Krajick & Sutherland, 2010; Pearson et al., 2010). Even though only some students will pursue careers in science, all will engage in reading about science during their lifetime. So, all students need to ‘read to learn’ in science!

Challenges Students with LDs Face when ‘Reading to Learn’ in Science

For many students with learning disabilities (LDs), reading is a challenge that may impact ‘reading to learn’. Science can be a particularly challenging subject, and parents should be aware of the factors that can make reading for science difficult:

Prior Knowledge – Students with LDs may experience challenges comprehending science texts if they lack prior or background knowledge of the presented concepts (Mason & Hedin, 2011). It is essential that all new concepts are explicitly linked to previous learning in order to make meaningful connections and allow the new information to make sense to these students.

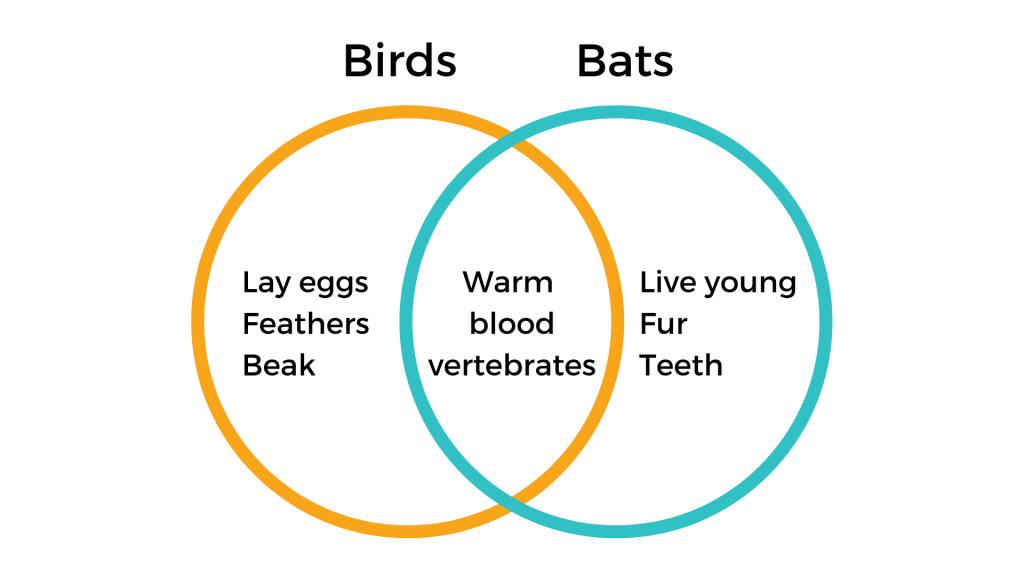

Working Memory – Students with LDs may have challenges remembering information while also performing other tasks. Science texts are dense with facts, concepts, and data to be remembered. When ‘reading to learn’ a science concept, the text might also present the reader with visuals such as a graph or an image to complement what the student has read. Coordinating these operations in working memory may be difficult for students with LDs (Dexter & Hughes, 2011). Click here to read the article An Introduction to Working Memory.

Vocabulary – Content-based text in science is rich in description but dense in vocabulary, due, in part, to the Latin and Greek roots (e.g., thermometer: Greek roots “therm” [heat] and “meter” [measure]) found in science vocabulary (Rasinski et al., 2008). Such vocabulary is often not phonetically regular, making the task of decoding challenging for students with LDs. As well, the technical use of science-specific vocabulary might be unfamiliar to students with LDs (Weiser, 2013). Click here to learn more about vocabulary and LDs for primary students.

Text Complexity – Readability of informational science texts varies depending on the format and text structures (Liang et al., 2013). Furthermore, science texts are considered conceptually dense; meaning many concepts are introduced at once. For students with LDs, science texts are complex both in their linguistic and cognitive features, and this can intensify comprehension demands (Kosanovich, 2013).

Key Strategies

Prior Knowledge

- In addition to reading, create hands-on activities that call back to some of your child’s knowledge.

- Example: To challenge the preconceptions of floating and density of fresh and saltwater, have students observe what happens when they place a fresh egg in a bowl of fresh water and then in a bowl of saltwater. What will happen to the egg if salt is added to the bowl of fresh water?

- Use guiding questions when reading to allow your child to make connections and focus on important aspects of the texts.

- Example: When reading about the habits of raccoons, ask them prior to reading what they think raccoons do at night, what they eat, etc. How does the text compare to their answers?

Working Memory

- Before reading, have your child use a graphic organizer that they can use to fill in information during and after reading a text. Click here to read the article Keeping School Work on Track: Staying Organized with Graphic Organizers.

Example:

- Use a memory mnemonic such as an acronym to help your child remember lists and other groups of information

Example: To aid in the recall of the: Watercycle (Runoff, Evaporation, Condensation, Precipitation) R=Really E=Excellent C=Coconut P=Pie

Vocabulary

- Pre-teach keywords and scientific terms. Use visual aids and concrete examples when possible.

- Example: Before teaching a unit on types of rocks (sedimentary, metamorphic, igneous), pre-teach vocabulary comparing and contrasting: magma & lava; sediment & particles; compacted & pressure.

- Look at the origins of words. Discuss the different roots, prefixes, and suffixes and their meanings.

- Example: The rock type, metamorphic, gets its name from the Latin word, metamorphosis meaning “transformation” with the prefix, “meta” (change), and base “morphe” (shape, form). Generate other words with the prefix, “meta” and base, “morphe.”

Text complexity

- Have your child use mental imagery to help them fully understand a text.

- Example: If reading about a specific animal and its habitat, have them draw a picture of the animal, based on what they have read. Ask them to label their drawing with details from the text.

- Explain to your child what “important” parts of the text are, such as a hypothesis, keywords, materials, results, and conclusions.

- Have your child highlight or underline what they think is important in a text. Discuss their choices with them.

Click here to read the article 5 Simple Tips to Help Your Child Acquire Reading Skills.

Click here to read the article Using Assistive Technology at Home for Literacy

References